reflection and inflections

Last Friday, we small cohort of postgrad arts students gathered in the late(ish) afternoon to meet each other formally, to welcome our newbies and to mark the beginning of the year. It is the last for some of us. No one here is in their first year bc of the policy to only give desks to those who have been here for a couple of years already. I call this the Test of Fortitude. If you make it through your first year without a dedicated desk or anywhere to put your research materials, that is, you managed to survive the ridiculous hot-desking arrangement while achieving some research, even writing, then someone will whisper in your ear that you’re probably eligible now for a desk of your very own.

A desk of your own. Anne Carson has acknowledged (The Iowa Review, 1997) having TWO desks at her home, one for scholarship, one for poetry.

When you finally walk into the top floor studio of the heritage listed John Woolley Building (1908) which has a lounge, a small kitchen and photocopy room, you want to cry at how very much like a proper university space it is. The style? Federation Arts and Crafts. The atmosphere? Well, in the main area with all our desks, supremely and wonderfully quiet but for the tap-tapping of computer keys, with the occasional rowdy roar of a University football home game being played on the oval next door.

I do harp on about the way the physical space of the work influences the work. I know this about me. But, if the University wants good, deep thinking and knowledge being produced, then to have their presumably deep-thinking academics wandering around the place looking for a desk to work at AND not be able to leave their materials there, then you’ll get work that reflects that: unfixed, peripatetic, even shallow work.

* * * *

I’ve been thinking about spaces of doing, in the case of something I wrote in the post on Thursday: I was talking about teaching myself Latin, and I wrote 'in the hope that it would help in writing, in learning languages.' They exist in some sort of concept of what it is to write, and of what it is to learn (in this case, another language).

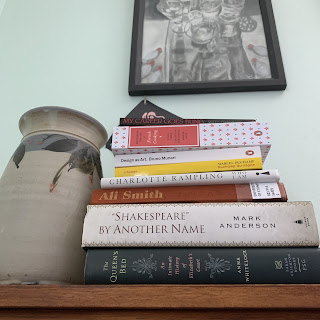

So, these two verbs—to write, to learn—have a sort of conceptual space around them: they are delineated by other words that we apply to the activity: writing, inscribing, sitting, typing, making sentences (there might be a desk at which writing takes place, a room, think perhaps of Emily Dickinson’s room or of Roald Dahl’s shed and worn chair with board to put over the knees to support the paper on which writing is performed).

As an associative link here is David Byrne’s lecture on ‘How architecture helped music evolve.’ This is more about writing for a space, rather than in a space. But it's a must see, in any case. DB is pretty wonderful, oui?

Last year, an artist friend and I talked about the abandoned rooms of the university and I’m thinking again now of taking walks through the campus and documenting these spaces that could (should) be used for creative work. There’s a magnificent old school hall right in the middle of one of the buildings. It has a stage, and the assembly part is huge. It sits at the heart of the building like a terrible figure for the administrative and organisational changes occurring in universities and in the knowledge hearts of contemporary societies. [Pictures to come]

* * * *

Yes. So, on Friday we met. Talked. I had bought some sparkling wine and some chips and some flowers for atmosphere. We now know each other’s names and projects. which range from Norse myths to Modernism and its foreground in Decadence, to IT in physical education, & to many others. Some have shared writing to get feedback. All is good.

* * * *

Last time I checked in (Thursday) I had scrutinised 13 of 27 numbered sections of Lisa Robertson’s 'Time in the Codex' (Nilling, 2012: 9-18). Please know that as of this afternoon I have scrutinised 25 of the 27 numbered sections (without taking into account the footnoted sections, which are dense essays in themselves and which I will look at after I finish the 27 and made some new sense of them). Something from my notes:

A suspension of ‘I.’

‘I’ is put on hold

or its physical presence

is shown

to be dispersed

--like suspended sediments in water--

in the space

between the thing and perception of the thing.

A book exists in slow time. To sense its POV

I’m a shadowing blur across its frame of reference.

Magnitude and movement.

By reading and responding our bodies become

expressive matter at a distinct scale and speed.

That is, measurable. And so, inscribable.

Comments

Post a Comment