On Reading Ali Smith's Autumn (2016) III

|

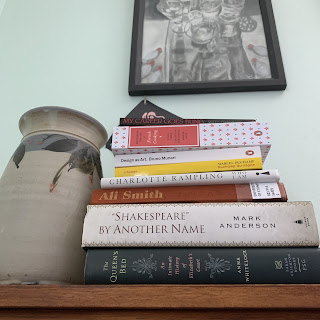

| Incidental book assemblage with vase and charcoal still life by me. |

Dear Void,

In yesterday's post I was consolidating my very first response to this text as I encountered it. First paragraphs are important to me. I stayed with Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things simply because, in its first contained paragraph, the air was fruity and stunned bluebottles died 'fatly baffled in the sun'. Fatly baffled in the sun. Fatly in the sun. Baffled bluebottles. Fatly. So, Autumn's 'the worst of times, the worst of times' gave me pause.

Something I've become aware of is that I automatically look for the structure of a paragraph before I commit to meaning-making from what is found on the page, and before I 'hear' any voice speaking the text. I'm a reluctant reader. I don't enter the reading contract very willingly. In the same way I don't give over my imaginative capacities very easily either. I'm a dreamer and enjoy my own thoughts.

Anyway, worst of times. Autumn is set within the time of our own living memory. Even so, the bracketed reminder that there is 'war on the news everyday' with images being presented of sieges and body bags rings mightier with the escalating events of the last two weeks and with the killing of so many people with 'especial violence' (118) being shared with us. Images on our tiny screens, in our flooded feeds. Will we become any less inured to this violence than we have become to the violence set upon Ukraine? I remember, we became collectively inured to the same sort of images coming out of Vietnam on the TV screens in our living rooms, at dinner time, in the seventies.

/

In my first post on reading Autumn, I included the complete first sentence from Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities as a way to bring the prior text more fully into my conversation with this new text. Ali Smith's deft use of the oft-sung 'selvaged' quote (best/worst times) announces Text's sometimes clumsy leap between prior text in disrepair and the way it interacts (in this state of disrepair) with both imagination and what exists around us.

Later Smith uses the quote, more fully this time, for one character to read to another 'quite quietly, out loud,' to awaken that other from a slumber (that slumber in which we shall sleep no more), or perhaps to entertain the slumberer's consciousness, to keep the wheels in there turning even as their body falls apart, as all things fall apart. They read more of the quote, they read beyond 'worst of times,' they read up to 'we had everything before us, we had nothing before us,' full stop. Smith has the character stop there, the rest of the sentence was, I suppose, not useful. 'The words had acted like a charm' (201). We didn't get to the end of the complete sentence, past all the clauses and to Dickens' observation that 'noisy authorities' insist the past is only ever superlatively comparative (best/worst).

Something I noted about my own imaginative capacities while I read (and listened along to the audiobook, a gift 'to the ear of the beholder' (93)): when a character's underwear looks like 'a boned blackbird' (92), I understood 'boned' to be as in 'boned corset' and spent a good moment trying to make the image and the text reconcile with surreal results. Please meet this incidental corseted bird newly arrive in my world. When we read, we are quite alone with the text. Not in charge of it. More in conversation with it. And while the text leads our imagination as we read, our imagination can always go its own way and often does. For better or corseted worse.

Jx

In preparation for a masterclass led by Deidre Lynch on Ali Smith's Seasons quartet next month at the University of Sydney. These are initial responses to the text with a gesture towards fidelity to quotations prompted by my research into commonplace books and the use of prior text.

I highly recommend reading Ali Smith's Autumn the first of four 'seasonal' texts. If you can't find a copy in your local secondhand store then, and only then, may you click here to find your copy at the Amazon store.

Comments

Post a Comment