Promises, promises.

Dear void,

We made it to Friday! Monday always promises there’ll be relief on Friday. And there it is!

(It’s Saturday afternoon now but I won’t go into details about how time slipped by so wastefully bc the purpose of this blog is not to complain to the void about having real-life responsibilities that have to be accommodated in the researcher’s dailiness, such as those I describe here and here. But I do wonder whether JL Austin ever had to buy office supplies and uniforms for his kid who was going back to school next week. And look, I’m relieved I never promised in writing to post daily!).

‘Promise’ is on my mind. I finished up Friday with one small page left on JL Austin’s Lecture I in How to Do Things with Words and I was pleased when he finally moved into a consideration of the utterance: ‘I promise’ as an example of a performative. I hoped he would. Indeed he calls ‘I promise’ an awe-inspiring performative that ought be spoken, then be taken, seriously.

Austin calls on Euripides’ text Hippolytus, to illustrate that ‘I promise’ involves an inwards act and an outwards expression of that act which is assumed to have a ‘spiritual shackle.’ That is, we understand that to give an oath, make a promise, is the serious description, true or not, of an inwards performance (comes from the heart) and these inwards and outwards events happen together (shackled). So, we may perceive that our tongue might take an oath but our heart might not. This Austin says, is a fictitious inward act. Weeding out some of these ‘fictitious inward acts’ from today’s marketing-led politics might benefit, well frankly the world, right?

‘I promise’ has an appearance of sincerity. And of self observance. The invisible had been observed, and presumably verified, in the ‘depths of ethical space’.

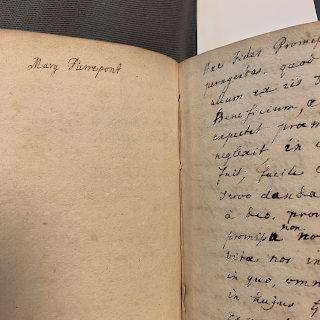

This amounts to a resonance with the object of my research, a commonplace book and its compiler, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (d.1762). [I took a bit of a conversational leap here which I’m sure you’ll forgive, void. There’s so much on my mind.]

In the second semester of my degree, early 2020, I took an introductory unit How to Read Latin (I have NEVER worked so hard or so happily in my life). I did this because Lady Mary’s commonplace book has a number of handwritten pages full of Latin which were 1) incomprehensible to me and 2) agonisingly seductive, pushing all of my you-can’t-have-this buttons.

The requirements for the Doctor of Arts degree at USyd ask that I complete 12 credit points in units of study. Preferably they be subjects that benefit the research. That’s my advice to new researchers. Look for something to feed back into your work in a meaningful way. Actually, I would give this advice to anybody planning a set of units that make up an arts degree, these sets will all be different for different people. Have some overarching goal or idea of the kinds of creative work you’d like to be producing. If you want to be a writer I highly, highly recommend taking a language, particularly an old language or a vulnerable language. You will see the way you use sentences and ways to use them anew. Words, after all, are your material. And to know how the material works is a good thing, surely?

So, with the end of Austin’s paper in sight, I’m planning to revisit the Latin pages of the commonplace book:

Haec Fides Promissorum, nos incitet ad conditiones

peragendas [CHK] . quod nisi fit, non possumus expactare

allum ex iis beneficium . . .

These promises, we will [?] encourage you [?] to perform as conditions [?]

Unless this happens [?] we cannot/not possible for us to expect [?]

|

| Detail of RBAddMs.35 folio 58r |

wHoo [stet] boy! Maybe I need to move beyond Chapter 6 of Learn to Read Latin by Keller & Russell. Lady Mary herself said (in conversation with Joseph Spence, citation to come) that she taught herself to read Latin at the age of 12! This would be around 1700. Although young girls were allowed, even encouraged, to translate from stoic philosopher Epictetus in Latin. There’s a good paper on this by Gillian Wright called ‘Women Reading Epictetus’ (again, citation to come. Look, it’s the weekend!).

I began this research process (in 2019) by transcribing the handwritten text into digital (therefore searchable) form, took the Latin in order to be able to read it for myself. That was in early 2020 which feels like a decade ago! Now I’m circling back with the idea of writing through the way, with my dribbling grasp of Latin, I can read/respond to the text.

If anyone reading this has Latin I’d welcome their feedback on my awkward translation above.

More to come, void. I promise.

J.

Comments

Post a Comment